A Proposal for Sensible Lot Sizes in Gainesville

A plan to make homes more affordable while preserving what we love about our neighborhoods

On Thursday, August 10th the Gainesville City Commission voted unanimously to start community engagement discussions around reforming lot sizes in Gainesville. It’s a proposal I brought forward to bridge the gap and find a common-sense compromise between those who say we need to build more homes and those who are worried about the impacts multifamily will have on their single-family neighborhoods.

Over these next few months I will be going out and educating the community and getting feedback. This blog post is meant to go into more detail, to explain what these changes mean and why it’s so critical for Gainesville to plan for our future and create more sensible standards for home building.

What the proposal does

This is a proposal designed as a middle ground between “the status quo” and “eliminate single-family zoning”. It allows single-family homes to be built in more diverse ways while maintaining single-family zoning by changing the city’s restrictions on lot sizes.

Essentially, the proposal legalizes small lot single-family homes like are common in historic neighborhoods like Duckpond and Pleasant Street, as well as new neighborhoods like Town of Tioga or Turkey Creek Forest, but are illegal to build across the vast majority of single-family zoned land in Gainesville.

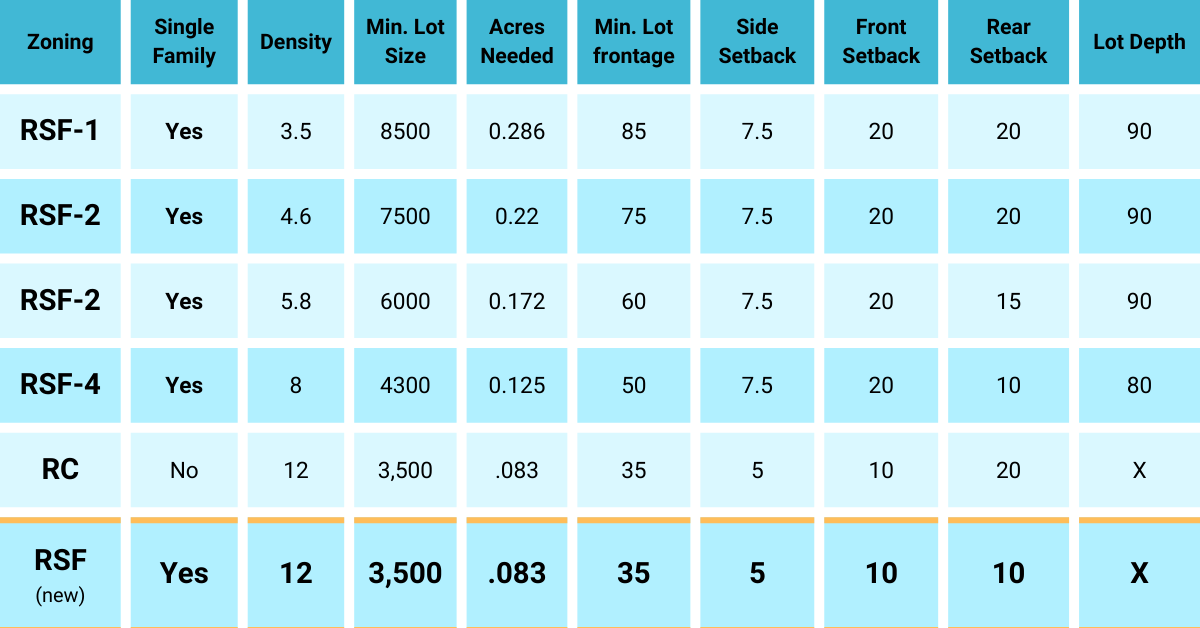

The proposal would take Gainesville’s four existing residential single-family zoning categories and merge them together into one. It would then give those areas the same lot dimension standards of “Residential Conservation”, which you can see in the Pleasant Street neighborhood just north of downtown.

Research shows reforms like these are critical to increasing the amount of affordable options for families, protecting our environment, reducing suburban sprawl and growing our local economy. But unlike the zoning change the previous commission passed, it is a much more modest reform, one that preserves single-family zoning.

I think it’s a good, common-sense proposal that is research-based, sensitive to the needs of our local neighborhoods, while modernizing a code that is very out of date.

The many benefits of legalizing smaller lots

Over the past few years there has been a flood of research and advocacy on zoning reform and the impacts that highly restrictive residential zoning has on communities.

Much of the conversation has been focused on “single-family zoning”, or the restriction against attaching multiple homes together through a shared wall. But lot size restrictions have been shown to be one of the most impactful zoning restrictions that reduces affordable options, hurts our environment, and increases sprawl.

That is why the Biden administration has called for more cities to reduce lot restrictions:

One of the most persistent factors depressing the supply of housing, especially entry-level and rental units, is exclusionary zoning laws and practices, like minimum lot size requirements, minimum square footage requirements, unnecessary parking requirements, prohibitions on or differing treatment for multi-family homes, accessory dwelling units, and manufactured housing, and limits on the height of buildings.

Senators Elizabeth Warren, Corey Booker, Bernie Sanders, and others are also in favor, sponsoring legislation to incentivize cities to lower their lot size restrictions.

Advocacy organizations like the Sierra Club, the AARP, the American Planning Association, Smart Growth America and many more have supported this change as well.

Building the homes people want

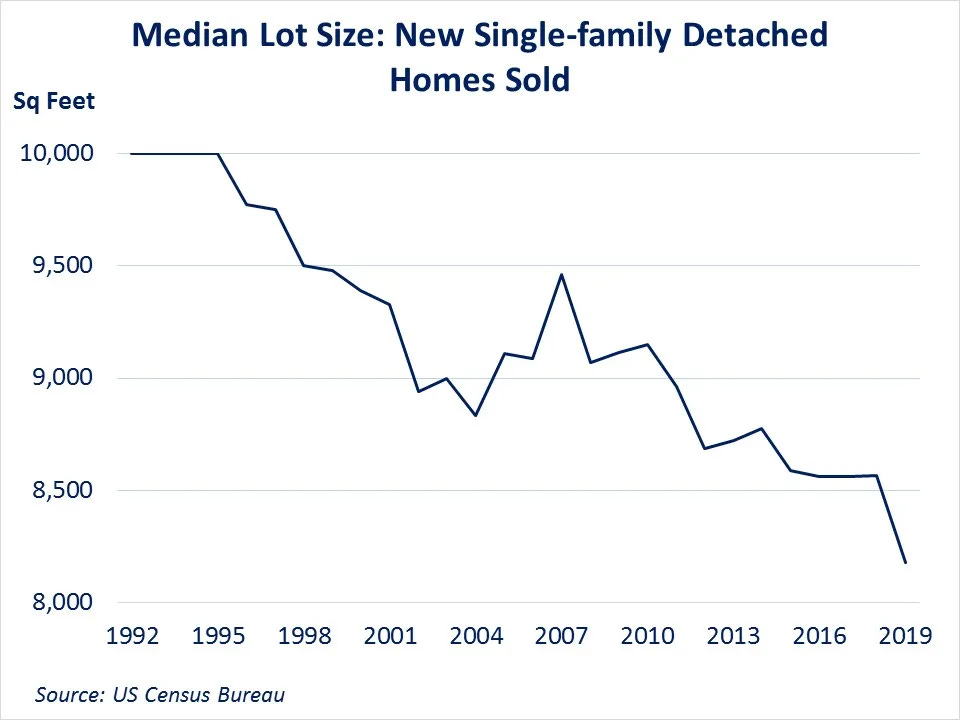

Home lot preferences have changed a lot since Gainesville adopted our single-family lot standards in the late 1950’s. The average lot size nationally has dropped significantly in that time, from .25 acres in the 1960’s to .18 acres today. If you’ve been to any of the new subdivisions west of I-75 you can see it for yourself. People are looking for more walkable suburban neighborhoods, and builders are building those for them.

But the homes people want in 2023 can’t be built in most of Gainesville. 86% of single-family land in Gainesville bans a standard .18 acre home from being built. In total, 69% of the single-family land is restricted to a minimum of .28 acres before any home can be built, a full 55% larger than the national median. Those restrictions are forcing families to live on lots larger than they otherwise want.

By giving the flexibility to build on smaller lots we are allowing families to live in the style of home that more people are wanting: less empty yard, more affordability, and more walkability.

More affordability across Gainesville

The average single-family home in Gainesville, according to the St. Louis Federal Reserve, was $484,190 last month, up from just $275,116 in 2016. That rapid increase has put homeownership out of reach for all except the richest of our residents. Something has to be done if we want a city where regular, working residents can afford to buy and live in a home.

Study after study has shown that mandating larger lot sizes means more expensive homes. A study by Harvard found, “One-acre increase in minimum lot size is associated with a 13 percent increase in housing prices, even for comparable house types.”

A Brookings Institute study found “[I]n places where land is expensive, building multiple homes on a given lot is the most direct way to reduce housing costs, because it spreads the cost of land across multiple homes.”

Desegregate Connecticut has a whole page of studies on the impact of minimum lot sizes if you’re interested.

More entertainingly than a page of studies, the news site Vox has a great video on how land use restrictions impact housing prices.

In it they directly discuss the impact of minimum lot sizes:

Another feature of many zoning laws is minimum lot sizes. It means builders are legally required to allot a minimum amount of land for each home, often a large amount of land. In Cupertino, most single-family lots must be at least 5,000 square feet each. Starter homes are usually around 1,400 to 1,500 square feet, and so you've basically banned all that type of housing. In Atherton, the minimum lot size for homes is one acre: more than 43,000 square feet, which makes it virtually impossible to build any kind of affordable home there. Together, exclusionary zoning laws like this push builders across the country to focus on bigger, luxury homes, instead of smaller starter homes, or multi-family housing.

Allowing more smaller, starter homes

Speaking of starter homes, as the New York Times points out in its article Whatever Happened to the Starter Home.

The nation has a deepening shortage of housing. But, more specifically, there isn’t enough of this housing: small, no-frills homes that would give a family new to the country or a young couple with student debt a foothold to build equity.

The reason for this loss is multi-faceted, but primarily because of zoning restrictions like Gainesville’s large minimum lot size, as the Times points out:

The simplest way to put entry-level housing on increasingly expensive land is to build a lot of it — to put two, three, four or more units on lots that for decades have been reserved for one home.

As land prices increase builders have two options: build a larger home on a larger lot to break into the “luxury” market, or build two smaller homes on a smaller lot. By mandating large lots, City code is mandating a future of larger, luxury homes, and making entry-level homeownership further and further out of reach.

Protecting our environment

More land for yards means less land for conservation and parks, more sprawl, and more dependence on automobiles. Larger homes also use significantly more electricity and water than smaller ones, exacerbating climate change and water depletion.

As Ethan Elkind, Director of the Climate Program at UC Berkeley Law School told NPR:

If you really want to address the climate problem, we're going to need our neighborhoods to be built in a different way, we just simply cannot meet our near-term and certainly our long-term climate goals unless we address the land use question.

That is why the National Sierra Club, along with numerous other environmental organizations and researchers, recommends reforms to minimum lot sizes in their urban infill policy guidance.

Growing a local, small builder economy

Gainesville was built through the work of small, local builders: the Parrishs, the Kirkpatricks, the Stringfellows. Local builders have a commitment to our local community, design in a way that fits the character of our community, and keep money local.

But increased regulations on building have hurt these small builders and essentially regulated them out of existence. Even worse, large-scale developers have tools to get around lot size restrictions that aren’t available to small infill builders: policies like planned developments and “cluster subdivions” which allows large-scale suburbs to build homes on the smaller lots people prefer, while local builders are stuck with outdated and onerous lot restrictions.

By allowing flexibility for building small-scale on lots city-wide we can put our local, small-scale builders on the same playing field as out-of-town developers, growing our local economy and building neighborhoods that fit the character of Gainesville.

The group “Strong Towns” is a proponent of small-scale, local building, and strongly recommends reducing lot size restrictions in order to bring back this local industry to towns like Gainesville. They go into more detail in their ebook: Unleash the Swarm: Reviving Small-Scale Development in America’s Cities.

What this means for our neighborhoods

All of this talk about data, allowances, setbacks and zoning restrictions can get a bit wonky. It’s worth talking about what a change like this means on the ground level for the neighborhoods we love.

Thankfully there’s an easy way to see that for yourself: go out for a walk.

Single-family zoning, along with these lot restrictions, came into effect in 1958. Any neighborhood that was in the City of Gainesville before 1958 grew without these onerous lot restrictions, and therefore more organically.

Take a walk through Duckpond. For over 100 years homes in this neighborhood changed and grew to fit the needs of the residents of that time without lot restrictions. In areas near downtown and the Thomas Center you’ll find more homes on smaller lots, as you walk north of Duckpond you’ll find more large lot, traditional suburban homes.

It’s never uniform though, and that’s a big part of the charm. You can find enormous half-an-acre colonial revivals alongside small starter homes all across the neighborhood. Instead of local government mandating cookie-cutter, one-size-fits all standards, the owners themselves decided what they wanted on their property, which changed depending on the preferences of the time and where their home was located.

That diversity of homes means a diversity of home prices and a diversity of families. You’ll find both more affordable starter homes, as well as some of the largest and most expensive homes in Gainesville. That’s meant Duckpond is a place you can find artists, young families, successful business leaders, and graduate students all near one another, able to live relatively affordably in a walkable community.

None of that required “eliminating single-family zoning” or spending large amounts of tax money on government subsidies for affordable housing. It only meant giving people a little more flexibility with what they can do on their property and giving it some time.

The same is true of my World War 2 era neighborhood of Oakview, which is more traditionally suburban but has small lot homes like mine (.13 acres) and large lot homes like my neighbor’s (.42 acres). The fact that my smaller home is side-by-side with their larger one hasn’t hurt our home values in the slightest: both of our homes have more than doubled in value in the last 7 years.

Go to any of the pre-war neighborhoods in old Gainesville: Grove Street, Pleasant Street, Bed & Breakfast District, Porters, College Park, Golfview. These are all very different neighborhoods, but they all share a bit more diversity and affordability due to being built prior to highly restrictive lot standards.

What this means for you: Meet the Hendersons

But that was then, what would that mean for today, and specifically for a typical resident? Imagine a family in Forest Ridge named the Henderson’s. They’ve lived in their 1970’s era prairie-style home since the early 1990’s. It’s a very standard home for these 1970’s era neighborhoods, 100 ft. wide by 150 ft. deep, resulting in a .34 acre home.

Their two kids left the house a few years ago, and while they have considered downsizing from their medium-sized home with a large lot, it’s not really been worth the headache to sell and move, especially with interest rates the way they are.

But over the holidays their son came home, left the gas stove on after cooking, which caught on a rag and spread throughout the home. Thankfully no one was hurt, but it caused tremendous damage to the kitchen and master bedroom, and the cost to fix is astronomical. They’re gonna have to do a full tear-down.

Under the current zoning the Henderson’s have two options: sell the empty lot or rebuild themselves on the existing lot. If they sell the .34 acre lot itself it is worth about $150,000, which they could put into a new home somewhere else. They could also rebuild the home, this time exactly as they’d like, with all the modern amenities they couldn’t get in their 1970’s era prairie home

The problem is that, as empty nesters, the Henderson’s don’t really want or need .34 acres of land nor a 2,100 sq. ft. home. They’d prefer the walkability of Haile, or maybe a little townhome in Cumberland Circle Communities. They’d also prefer a little less yard work.

As much as they love Forest Ridge and all their neighbors, the thought of building another huge single-family home on ⅓ of an acre lot is daunting, and far more than the two of them need. A little starter home in Forest Ridge would be ideal, but that’s not allowed or economically viable under our current zoning code.

Whatever goes into their home’s place will be much larger than what was there before: homes have doubled in size since the 1970’s, so while their 2,100 sq. ft. home would have been “luxury” in 1974, today a home on a big lot like that is going to be more like 3,500 sq. ft. It wouldn’t make sense to build anything much smaller considering the land underneath is $150,000.

Under my new proposal they would have a third option: split the lot and build two smaller homes on it instead. Due to the restrictions of a 35 ft. lot frontage they wouldn’t be able to split it into three, since they would need a minimum of 105 ft. to make that happen. But they can create two 50 ft x 150 ft lots, which are common in Gainesville, and would give two homes of .172 acres, which is perfect for them and a family next door. That is a very popular size of lot, just under the median nationally for new lot sizes, .18 acres.

By choosing to split the lot and create two homes instead of one the Henderson’s have been able to stay in the neighborhood they love, reduced the amount of yard work they need to do, given a home to a family that wouldn’t have had one before, and brought in a new neighbor that can enjoy the great neighborhood of Forest Ridge. They also made about $80,000 from the deal, which can go toward retirement savings or to alleviate those big out-of-state tuition payments they now have.

The alternative would have certainly been a much larger home than was there before, or a “McMansion”, on a lot that had more space than the Henderson’s really wanted.

Doing a teardown wouldn’t have made sense economically without the fire happening: the home before was worth $500,000 and they’ll never make that up through tearing down a perfectly good home, but at the end of the home’s useful life they have more options for what they can do that makes more sense for them, and brings more affordable housing to Gainesville.

Something needs to happen

In the blink of an eye the cost of housing has skyrocketed and made our city unaffordable. I hear it every day from families looking for homes: there are too few of them, they are too expensive, and they get bought up within hours. The fact is that Gainesville has grown by 4,794 people in the past two years, one of the fastest-growing cities in Florida. If we want to be a city where artists, teachers, firefighters, musicians, cooks, and hairdressers can live we have to plan our city for that growth and come up with new ways to design our community.

But it doesn’t have to be the divisive process of last year’s zoning code change. We can still preserve the neighborhoods we love, listen to our neighbors, and find ways where we all benefit from change. By looking to the past we can come up with a better future: more flexibility, more rights given to property owners, and more diversity of homes choices. All while protecting single-family zoning.

Where we go from here

Over these next few months I will be personally going out and educating and soliciting feedback on this proposal. There will be two city-held meetings on both the East and West sides of town. I will also be going to community groups to discuss the proposal and receiving feedback from them. Those aren’t scheduled yet, but I’ll update this portion of the website to let you know when it is upcoming.

After that it will come back to the City Commission for a vote which, if successful, will be sent to the City Plan Board for review. If they successfully approve it it will come back to the City Commission for approval.

My hope is to do community engagement a bit better than it’s been done in the past. Instead of relying on staff to go around and talk about my proposal I’m doing it myself, putting feet to the ground and meeting with community groups. Instead of flashy campaigns it’s more conversations and a lot more listening.

Call me naive, but I believe we can find common ground and real solutions on this issue. I believe our community wants to solve these issues, is open to new ideas, and wants to see Gainesville be more affordable and vibrant.

I’m under no illusion it will be easy: making changes to neighborhood zoning never is, but I believe it is possible. And more importantly, it’s necessary.

If you want to chat please email me eastmanbm@cityofgainesville.org or call my cell phone 352.756.7280. I’d love to come chat with any group interested in learning more.

Subscribe to gVille

Newsletter for Bryan Eastman, Gainesville City Commissioner District 4. Longer form dives into what the city is doing, why we're doing it, and the policies we should be pursuing.

We are not in favor of this for existing neighborhoods. Please do not destroy Gainesville any more and please stop trying to turn Gainesville into a big city. It is appalling, cruel and inconsiderate how residents have been affected by recent constructions.

Okay thanks for getting back to me 😊